As professionals working passionately to promote forest health and protect communities from wildfire, we are compelled to provide a response to the letter to the editor that was published July 10, 2023 that perpetuates misinformation*. In California, much of this misinformation relies on a small body of agenda-driven science that has been rebutted in many scientific journals (Jones et al. 2022, Jones et al. 2019., Levine et al 2019; Safford and Stevens 2017).

There is no question that home hardening and defensible space are critical and necessary actions that residents should take to improve home survival in wildfire-prone areas (Quarles et al. 2010; Valachovic et al. 2021) The Plumas County Fire Safe Council has developed and offered programs to promote wildfire preparedness and improve defensible space for residents for 20 years; largely funded with local, private, state, and federal grants. In addition, the Fire Safe Council is working with Plumas County to establish a Home Hardening Incentive program.

However, your home is the last line of defense against a wildfire, and our rural communities are set within forests that will continue to burn. There were homes in Greenville that had impeccable defensible space and home hardening that did not survive extreme high severity fire events during the Dixie Fire. In fact, the 2019-2021 wildfires have resulted in large areas of high severity fire in Plumas County, now dominated by dead trees and resprouting shrubs, which local forest and fire ecologists have shown create novel fuel-loaded conditions that have the potential to reburn at high severity (Coppoletta et al. 2016).

Some wildfire misinformation originates from distilling complex wildfire science into generalizations that rarely apply everywhere. Oversimplification of complex wildfire causes and consequences […] muddies public perceptions of appropriate management. From Jones et al. 2022

The thrust of the misinformation about forest health relies on the concept that “forests that are denser actually burn slower as they hold moisture better and act as windbreaks.” Dense conifer forests provide continuous fuels from the surface to the tree canopies, contributing to the potential for crown fire. Crown fires are the most difficult and dangerous to suppress, create embers that threaten homes, and – at the scale and severity of the wildfires that we are seeing in recent years – are likely to irreversibly convert forest into shrubland.

In the arid conifer forests of California, and particularly under the effects of a changing climate, wildfires are not the only forest disturbance that has the potential to impact our communities. In 2012-2016, over 129 million trees died in the central and southern Sierra Nevada range due to drought induced bark beetle epidemic which created conditions fueling mass fire behavior the 2021 Creek Fire (Stephens et al 2021). Last year on the Plumas National Forest alone, an estimated 1.6 million trees died across approximately 110,000 acres of the remaining green forests outside of the wildfire footprints (USDA Forest Service Forest Health 2022). This should be concerning to us all. In the past decade in the southern Sierra, drought, associated bark beetle epidemic, and wildfires have resulted in a 30% loss of forest cover across the region (Steel et al.2023) We are on a similar track in the northern Sierra, over the past 5 years 16% of conifer forests have been lost due to wildfires (USDA Forest Service Ecology Program 2022). This is a conservative estimate as it does not include forest loss from past large fires on the Plumas NF like 2000 Storrie, the 2007 Antelope Complex or Moonlight Fires, or the 2012 Chips fire. Much of this forest loss has impacted mature forests whose large diameter trees are the backbone of these dry frequent fire forest ecosystems.

While these trends have been positively linked to climate change induced shifts, the root of these high severity wildfire and tree mortality events are forests that are far too dense due to over a century of fire exclusion. Historic forests, which are thought to be more resilient, were very open in general, had only 20-30 mature trees per acre, and burned far more frequently every 6-7 years – This resilient forest structure was maintained by centuries of repeated and frequent fire. Today’s forests are far denser, have more than 140 – even up to 500 trees per acre, and many haven’t burned for over a century (North et al 2022). In most cases, simply re-introducing one underburn to these very dense forests will not be effective in creating forest structure resilient (Stephens et al 2021; Steel et al 2021).

Even more concerning is that time is running out: Recent climate research in the Sierra Nevada suggests that by 2040-2069, predicted climate may only be able to sustain 25% of the aboveground live biomass we see today (Bernal et al. 2022) – we will need both mechanical thinning and managed and prescribed fire to build resilience in these forests. There is no time to waste – these forests need to be restored.

Healthy, fire-resilient communities are dependent on healthy fire-resilient forests. This provides the opportunity not only to mitigate wildfires before they enter communities, but also the opportunity to manage fires for long-term forest restoration and ecological benefit. Again, local science has shown fuel reduction and forest restoration, including mechanical thinning and prescribed fire, are not only effective (Low et al 2023), but also necessary tools to manage forests for ecological and community resilience (North et al. 2021).

As forest and fire ecologists, managers, and practitioners, we recognize that we need “all the tools in the toolbox” including the suite of treatment methods that Plumas National Forest proposes in the Community Protection – Central and West Slope Communities Project. If long term management that significantly incorporates the use of fire is to become a reality, these initial treatments are necessary to increase the opportunity for the use of beneficial fire across the landscape. Locally, the Plumas Underburn Cooperative was founded to engage the public in the safe and effective use of fire and increase support for agencies’ prescribed fire programs. As practitioners engaged in these efforts, we have encountered the level of complexity required to effectively use prescribed fire as a restoration tool. And, as practitioners who value the unique ecological benefits of prescribed fire, not one of us is of the opinion that it could be used exclusively for restoration.

It is well documented that there are unprecedented levels of high severity fire (Williams et al 2023) AND unprecedented levels of drought induced tree mortality in the Sierra Nevada which are contributing to landscape level forest loss across the range (Steel et al. 2023). It is also well documented that forest management at the state and federal level isn’t happening at large enough scale to meet forest restoration goals (Knight et al. 2021). The forest products and fire management industries are both critical partners in accomplishing these much needed restoration treatments. Mechanical thinning – which includes tree harvesting (ie. Logging) facilitates restoration of forest structure AND reintroduction of fire. Prior to the 2020/2021 fire seasons, and certainly after them, there was more need for restoration by mechanical thinning than there was milling infrastructure to take the trees that need to be removed. Contemporary fuel reduction and forest restoration projects are not a boon for the logging industry, as has been suggested, because the industry has already been grappling with more material than it has had the capacity to process and market. We need growth in both forest products and prescribed and managed fire management to meet our forest restoration needs.

If anything, the Plumas Community Protection – Central and West Slope Communities Project doesn’t treat enough acres, but this represents a much needed first step.

Plumas County is known for its notable history in collaborative forestry and many of us who have dedicated our careers to forest conservation and management recognize the importance of working lands conservation. Perhaps most disconcerting is that the threats to these forests that we used to write about in concept (e.g. mega-fire behavior, unprecedented drought and tree mortality, and loss of forest ecosystems) are now realities and the impacts of the past few years are clear. Passive management strategies have been ineffective in protecting forests, and conserving forests in the 21st century will require active forest management at much larger scales – otherwise these forests may transition to other vegetation types and high severity fire regimes within our lifetimes.

We have inherited a landscape in crisis. The scale and scope of the response must be in-line with the magnitude of that crisis. The proposed Forest service project is not the ultimate solution, it is the emergency action required to give us opportunities for resilient, healthy forests and rural communities into the future.

We further encourage the public to provide comments regarding the Community Protection – Central and West Slope Communities Project.

Ryan Tompkins

Forester & Natural Resources Advisor, RPF No. 3108

University of California Cooperative Extension

Plumas, Sierra, and Lassen Counties

Hannah Hepner

Program Director, Plumas County Fire Safe Council

Michael Hall

District Manager, Feather River Resource Conservation District

Trina Cunningham

Mountain Maidu

*“Misinformation is incorrect or misleading evidence or discourse that counters best available science or expert consensus on a topic (Vraga and Bode 2020). Misinformation often includes partial truths, which are central to its successful spread. By obstructing solutions to […] environmental issues, misinformation deters effective policy responses to societal threats. Misinformation confuses people about the causes, contexts, and impacts of wildfire and substantially hinders society’s ability to proactively adapt to and plan for inevitable future fires.” From Jones et al. 2022

Prior to treatment, the Butterfly Twain project had an average of 725 trees per acre, generally of small size. Historically, the site would have had well below 50 trees per acre, of larger fire-resistant trees. Photo by D. Kinateder

These photos are representative of the forest structure after the Butterfly Twain Fuels Reduction and Landscape Restoration project, which included hand thinning, mechanical treatment, and prescribed fire. Photos by D. Kinateder & H. Hepner

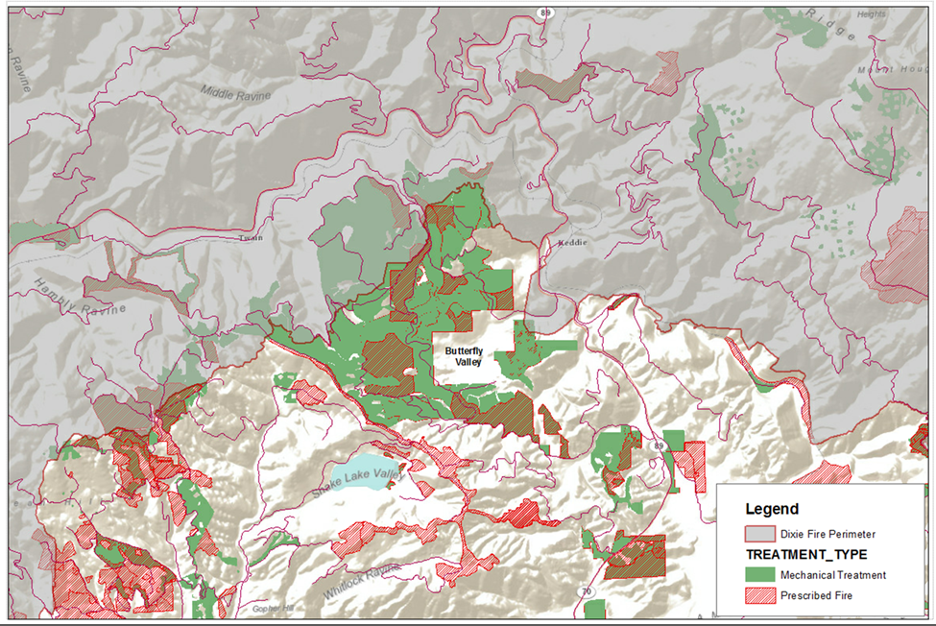

This map shows where the treatments in the Butterfly Twain project interacted with the Dixie Fire. The fire extinguished or moderated at the project boundary, in some cases without any suppression resources present. Many of the prescribed fire projects shown here were facilitated by mechanical thinning treatments that occurred in the past 20 years thanks to the Herger-Feinstein Quincy Library Group Pilot Project.

This photo highlights the difference in snowpack accumulation that reaches the ground in untreated (left) and treated (right) forests. In the treated area, snow is able to reach the surface where it melts more slowly and enters the Upper Feather River watershed, whereas in denser untreated areas snow is intercepted in the canopy and evaporates before it has the opportunity to enter the watershed (Hardage 2022, Krogh et al 2020). Photo by D. Kinateder

Article link: https://www.plumasnews.com/where-we-stand-forest-management-needs-to-happen-at-much-larger-scales/